- You are here:

- Home

- About Symbols

- Helping refugee pupils develop the building blocks of language

Helping refugee pupils develop the building blocks of language

There are many different ways to help child refugees learn English says Sue White, former teacher, local government advisor and senior educational specialist at Widgit.

Starting a new school can be daunting for any child. Every school has effective strategies in place to make it easier for children coming into an unfamiliar learning environment for the first time to feel comfortable, make friends and be ready to learn.

But for a child refugee, who could potentially have left family and friends in their homeland and may speak no English, there will be multiple hurdles to overcome in addition to learning a new language.

Currently 1.6 million children who do not speak English as their first language are being supported by UK schools. With child refugees arriving through Afghan resettlement schemes or escaping conflict in Syria or Ukraine, this figure is likely to increase.

So, what can schools do to help ensure these children develop the English language they need to access the curriculum and engage fully in school life?

Below are six strategies to help schools meet the needs of child refugees and other pupils with English as an additional language (EAL).

Try Widgit for free to help all EAL children improve their literacy attainment.

1. Launch a learning buddy scheme

Children with limited English can be quickly overwhelmed by an unfamiliar classroom but providing a learning buddy can be a simple way to reduce anxiety and help them be ready to learn.

A friendly child with good communication skills will help a new pupil to feel welcome in unusual surroundings. A learning buddy will also be able to show the child where to store their belongings, find the equipment they need for lessons, locate the lunch hall or nearest toilets, helping them to settle in and become more independent.

It can be useful to seat children who have yet to develop a wide range of English vocabulary close to the front of the class, where they can see facial expressions more clearly. This will improve their ability to understand the English being used by their teacher and help them to pick up the subtle physical gestures that are the building blocks of a new language.

2. Employ some simple changes to teaching practice

Try to add simpler language, where appropriate, in lessons which include child refugees who have little English. This will help to prevent pupils from disengaging if they don’t fully understand what’s going on.

Using a phrase such as ‘hotter world’ alongside ‘global warming’ in a geography lesson, for example, will give EAL children a starting point from which they can develop more complex language without missing the context of the learning.

You may want to ensure more time is factored into lessons for pupils who don’t speak English to process instructions or respond to questions they are asked too.

It can often take longer for a child to translate from English into their native language and then back into English before they respond. Allowing them some extra time will reduce stress, encourage them to take part in classroom activities and help to ensure lessons continue to run smoothly.

3. Encourage children to speak their native language

It may seem counter-intuitive but allowing children who are in the process of learning English to use their first language can be very positive.

Teachers could encourage children with refugee status to answer questions in their first language in lessons, for example. This may simply help to put a child at ease if they are in the very early stages in their development of English and prevent them from feeling isolated from the rest of the class for fear of responding incorrectly.

But as their spoken and written English improves, they will gain the confidence to use more words or form more complex sentences. They will then be more likely to participate not only in lessons, but also embrace the extra-curricular opportunities the school offers. Engaging fully in every aspect of school life is vital for sparking new friendships and uncovering a child’s individual talents and interests whether they love to play chess, take part in team sports or get involved in the arts.

4. Make school life more visual

Once words are spoken, they disappear. Instructions written in English are difficult for children with limited English to interpret too, so they are less likely to engage in learning or group tasks.

Using visual prompts such as symbols in school can be a quick and easy way to help pupils with EAL to build the vocabulary they need to progress. Symbols reduce anxiety by giving children a permanent reminder of language that is focussed on the specific message you are trying to get across. They give a child a sense of independence and belonging too, as they can join in activities without requiring as much adult support.

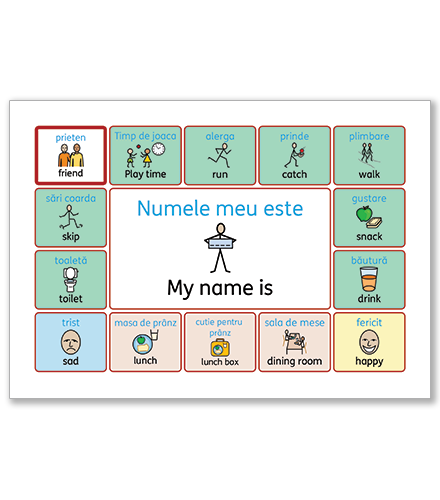

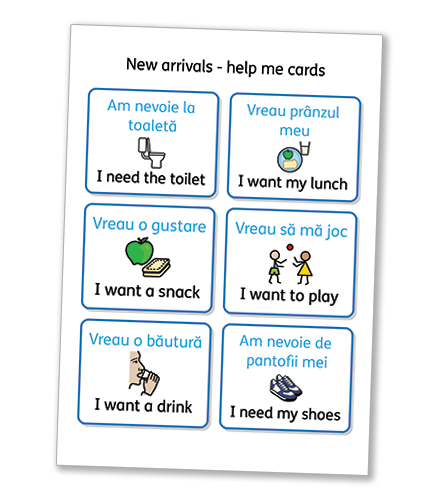

You could create vocabulary charts containing essential school phrases such as ‘copy,’ ‘underline’ or ‘I need the toilet’, for example, and include a symbol to represent each phrase. Adding the words in English as well as the child’s native language will help them communicate and better understand what you are asking them to do, as in the examples shown in this article, designed for supporting children whose first language is Romanian.

Symbols can be used to help scaffold learning tasks too, providing structured activities children can complete independently, boosting self-esteem.

5. Pre-teach vocabulary

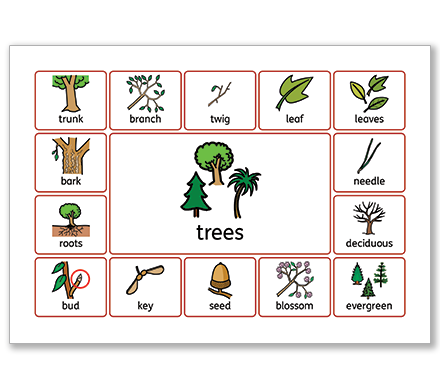

Using symbols to pre-teach some of the words and phrases which will be used in a forthcoming lesson is a great way to give a child with limited English a head start in their learning.

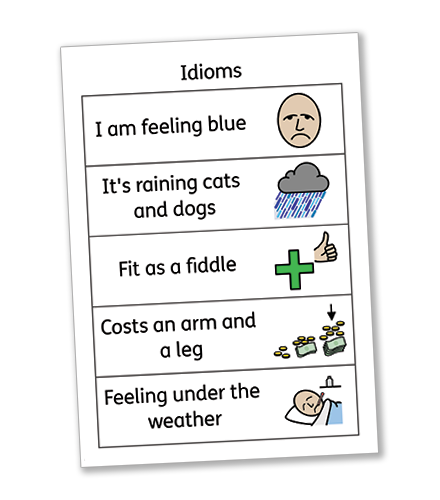

Teachers could provide a visual representation of concepts, idioms or common English vernacular, which a child refugee may not be familiar with, in advance. So, if the class is due to discuss a story featuring ‘the rainbow-coloured brolly’, a symbol of a rainbow alongside an umbrella could be shared in advance to help explain the topic in a very visual way.

Similarly, subject-specific language could be taught prior to a lesson using symbols to explain words such as ‘friction’, ‘gravity’ and ‘battery’ that a child might come across in science, for example. These resources would work for all children, not just those with EAL, helping to ensure classrooms are inclusive places to learn.

6. Build home-school links

Another way for schools to support EAL pupils is to make it easier for parents and carers with limited English to provide effective support from home and symbols have a role to play here too.

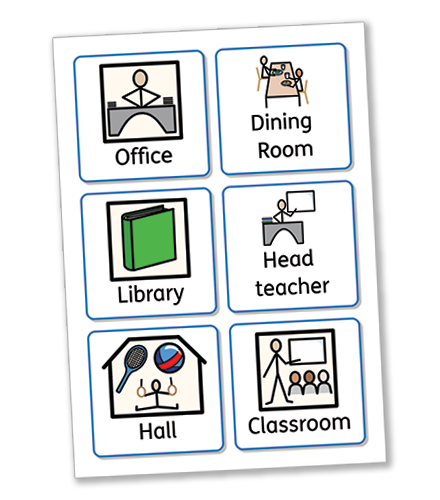

When used in and around school, symbols help parents navigate their way around easily. So, you might include a symbol of a book on directions to the library or a plate for the dinner hall. Symbolic imagery can also be included in the school’s policies or in the newsletter, making them simpler for non-English speaking families to interpret.

Every child deserves the best possible education, wherever in the world they happen to come from. With a few minor adjustments, your school can better support child refugees, help build their understanding and learning of English and open up the very real possibility of a much brighter future.

Try Widgit for free to see how you could improve literacy attainment in children with EAL.